- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- El Brujo and the exchange of exotic objects

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Jose Ismael Alva Ch.

By Jose Ismael Alva Ch

Resident Archaeologist of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex

What is exchange? Exchange is the human activity that allows the obtaining of raw materials and processed objects from different geographical regions. Said activity is carried out under reciprocal conditions between human groups, seeking a certain equity and equivalence that is valued socially.

The diversity of ecological floors and ecosystems of the Andes drove its different settled societies to exchange food, natural resources and special objects, among others. This guaranteed complementing the consumption of products of certain ethnic groups, with others generated in distant areas.

Exotic goods

The economy in the ancient Andes, as others throughout the world, was developed around products that allowed a varied consumption of subsistence products. However, there was also the production and circulation of objects prominent in social life. These objects enjoyed a special position in the exchanges, given that they came from very distant areas (which is why they were considered to be rare) and over time had been assigned an exclusive meaning within the narratives of native power and authority.

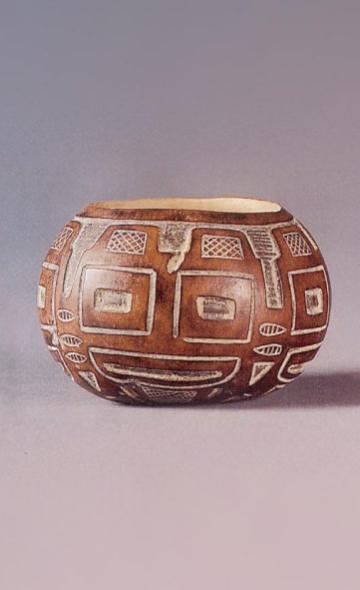

Main exotic goods in the El Brujo Archaeological Complex

The El Brujo Archaeological Complex, located on the coastline of the Chicama Valley, is a testimony to the continuous human occupation on the northern Andean coast, which dates back to 14,000 years before the present time. At different stages of the history of El Brujo, we identified the presence of colorful feathers (possibly from jungle birds), obsidian and metals such as gold and silver. But, exceptionally, it has been documented that the spondylus valves appear as offerings in ceremonial contexts of Huaca Cao Viejo during the Mochica period (200-800 AD); moreover, cinnabar had an extensive use in the preparation of the funerary bundle of the Lady of Cao, the Mochica elite personage of the highest hierarchy level so far recovered archaeologically in the Chicama Valley.

Next, we will investigate the history of some of these objects.

The Spondylus

It is a mollusk of the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean, which is distributed from the Gulf of California in the north to the Bay of Sechura (Piura, Peru) in the south. To obtain it, it is necessary to dive between 6 and 30 meters deep, which is why the collectors must be expert swimmers (Gorriti, 1998, p. 11). From early times, this red shell was appreciated for the belief that its presence stimulated the rains and regenerated the waters of the rivers, indispensable for agriculture in the Andes.

The earliest evidence of Spondylus in the central Andean region is at the preceramic sites of Caral and Los Gavilanes on the north-central coast of Peru (Gorriti, 1998). In the period of Tahuantinsuyu (fifteenth and sixteenth centuries AD), the lordship of Chincha was known for the presence of merchants who were in charge of the distribution of this mollusk for their consumption in palaces and temples of the Andes (Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, 1970).

Cinnabar

It is the mercury sulfide mineral whose only known deposit is in the heights of present Huancavelica. The bright red color of this mineral made it to be estimated above other pigments such as hematite (iron oxide), which was somewhat easier to find (Ramos Vargas, 2004). However, cinnabar is highly toxic when pulverized to obtain pigment, as mercury particles enter the body through the skin and respiratory tract, seriously affecting the nervous system (Fernández, 2016).

Records on the use of cinnabar date from at least the Formative period (1800-200 BC), given that several temples in the northern sierra of Peru show its use to decorate luxurious ceramic vessels (Ramos Vargas, 2004). In the Mochica period (200-800 AD), cinnabar was used to completely cover the body of the Lady of Cao within a mortuary ritual that preceded funerary bundling; moreover, sections of the beginning of each stage of the bundle (represented by embroidered faces) were also covered by dust from this mineral (Mujica, 2007).

Final comments

The exchanges of exotic goods in the Andes required remarkable efforts in the collection/extraction of raw materials, the long transport by rafts and in large caravans of llamas, as well as the intervention of artisans and other specialists in the transformation of those raw materials into luxurious products for a privileged consumption associated with elites and ethnic leaders. These objects, eye-catching and rare, are therefore the product of the participation of multiple actors in these exchange systems, which archaeologists seek to identify and understand within our vast pre-Hispanic history.

Bibliographic References

- Fernandez, Y. (2016). Deadly beauty: These are the most dangerous minerals that you can find. Magnet.

- Gorriti, M. (1998). Marine mollusks: Spondylus, strombus and conus. Their meaning in Andean societies. Bulletin of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1(4), 10-21.

- Mujica, E. (Ed.). (2007). El Brujo: Huaca Cao, Moche ceremonial center in the Chicama Valley. Wiese Foundation.

- Ramos Vargas, M. A. (2004). Cinnabar in the Central Andes. Notes to understand its context. Journal of Research of the Archaeology Students Center, UNMSM, 6, 157-182.

- Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, M. (1970). Merchants of the Chincha Valley in Pre-Hispanic Times: One Document and some comments. Spanish Journal of American Anthropology, 5, 135-178.

Researchers , outstanding news